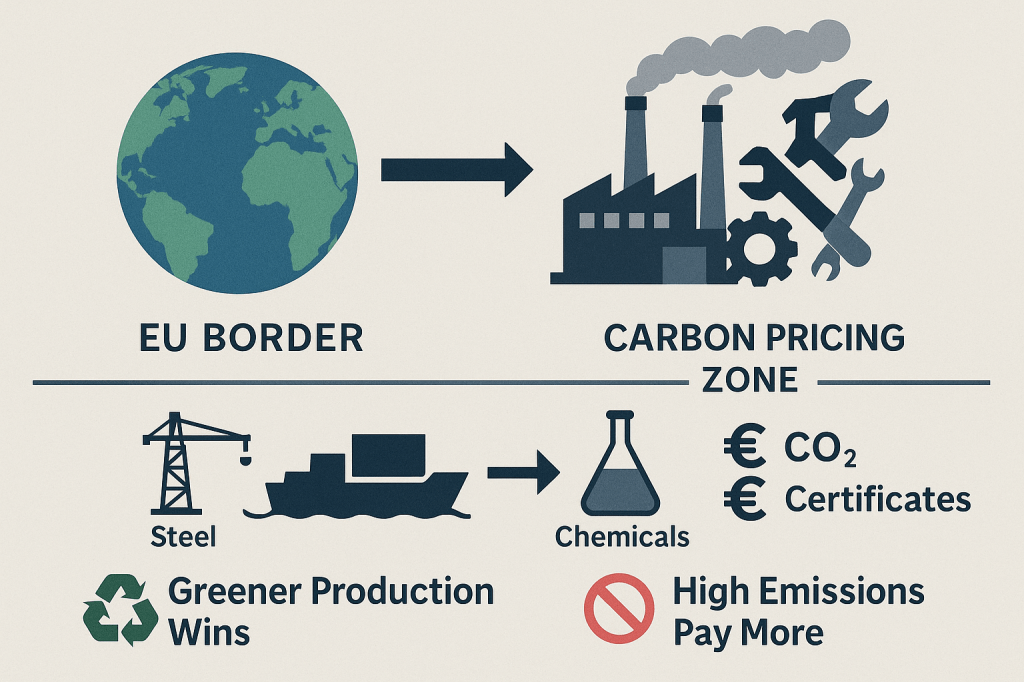

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) represents one of the most consequential policy shifts in global trade architecture since the creation of the WTO. Historically, carbon pricing and emissions regulations remained domestic frameworks—shaping domestic industries but sparing international exporters. CBAM breaks that boundary. By putting a price on the carbon embedded in imported goods, it essentially extends the EU carbon market beyond its borders. The transition began in October 2023 with mandatory reporting and will move into full financial enforcement by 2026. The mechanism is designed to prevent “carbon leakage” — the relocation of production to countries with weaker environmental laws — and to synchronize global producers with the costs borne by EU industries under the Emissions Trading System.

Steel: The First Frontline of Carbon-Linked Trade Policy

The steel sector sits at the center of CBAM’s early implementation stage. Importers must now declare total embedded emissions from the production process and pay a carbon cost that mirrors the EU ETS price—hovering near €78 per tonne of CO₂ in 2024. Historically, steel has relied on energy-intensive blast furnaces; in emerging economies, this often means coal-based manufacturing. CBAM reshapes that model.

Projections suggest EU steel imports could decline by nearly a quarter by 2034 as costs erode the price competitiveness of exporters from nations like India, Turkey, and China. Larger steel companies with access to green hydrogen, electric arc furnaces, or carbon capture technologies may pivot successfully. But small and medium manufacturers risk exclusion not because of price alone — but because of reporting burdens, verification requirements, and lack of technical capacity.

Updates in 2025 introduced a 50-tonne de minimis exemption to reduce administrative load on micro-importers, but the scope is expected to expand to downstream steel products by 2026, tightening the compliance perimeter.

The historical irony is stark: for decades, Europe imported low-cost steel from regions with more carbon-intensive energy systems. Now, the price signal is reversing the flow—turning sustainability into an entry requirement rather than a niche premium.

Chemicals: The Slow but Fundamental Expansion

While the steel sector faces immediate pressure, the chemical sector is navigating a gradual but transformative CBAM timetable. Hydrogen, nitric acid, and ammonia are already included. Organic chemicals, polymers, and petrochemical derivatives will phase in between 2026 and 2030, reflecting a complex balancing act between global supply chains and trade diplomacy.

Chemical producers in Europe benefited from free EU ETS allowances worth approximately €13 billion in 2023 — a buffer that foreign exporters never had. Once these supports decline, CBAM becomes a levelling mechanism but also a geopolitical disruptor. Producers in regions dependent on fossil fuels — such as the Middle East, South Asia, and parts of the U.S. Gulf Coast — will face significant cost escalations.

The policy forces deep tracking of emissions intensity across value chains. For many exporters, the true challenge is not the carbon price — it is the measurement, reporting, and verification demanded by EU rules. The digitalization of emissions reporting could reshape the governance framework of global chemical trade.

Trade Effects: Fragmentation or Green Convergence?

Economic models predict that CBAM may slightly contract EU GDP by 2030 — around 0.22%. But the policy’s strategic goal is not short-term growth; it is long-term decarbonization combined with trade leverage. Through what analysts call the “Brussels Effect”, CBAM may evolve into a global standard in the same way GDPR reshaped data governance.

Emerging economies—including India, South Africa, Indonesia, and Brazil—are responding with parallel strategies:

acceleration of domestic green hydrogen missions

development of green steel certification systems

search for alternative markets such as Africa and Southeast Asia

diplomatic pressure for exemptions or revenue-sharing

As part of ongoing 2025 consultations, the EU is evaluating whether exporters can deduct equivalent domestic carbon taxes — hinting at the emergence of a global carbon price alignment system.

There are real risks: loss of export competitiveness, job displacement in carbon-intensive clusters, and unequal compliance burdens. Yet CBAM revenue could eventually fund clean-technology transfers — turning what is currently seen as trade pressure into climate partnership.

A Glimpse Into the Future

By 2030, carbon may no longer be just an environmental metric — it may evolve into a currency of global trade compliance, much like safety standards or intellectual property protections. CBAM signals a world where market access depends not only on price and quality but on climate alignment.

The historical evolution—from post-war industrial capacity to globalization and now to carbon-regulated trade—suggests that sustainability may become the new axis of comparative advantage. Nations investing early in green infrastructure, renewables, hydrogen systems, and circular industrial models may gain strategic dominance, while those slow to transition risk marginalization in high-value trade.

CBAM is not just a policy—it is a preview of a new industrial era. One where carbon efficiency becomes a determinant of competitiveness, supply chains reorganize around climate mandates, and trade rules evolve to integrate sustainability as a core condition rather than an external concern. The next decade will determine whether CBAM catalyzes fair green industrialization or deepens global trade asymmetries. Either way, the carbon border era has begun.

#CarbonBorderAdjustment

#GreenSteel

#ETSCompliance

#TradeDecarbonisation

#IndustrialTransition

#CarbonLeakage

#SustainableChemicals

#GlobalSupplyChains

#ClimateTradePolicy

#BrusselsEffect

Leave a comment