In the early 2000s, as sustainability frameworks gained traction globally, RMIT’s Centre for Design in Australia took a pioneering step. In 2003, it released a landmark discussion paper addressing the relationship between the waste management hierarchy and broader sustainability goals for the Victorian Government. Co-authored by Helen Lewis and John Gertsakis, the paper laid a critical foundation for understanding how strategic waste management could drive resource productivity, minimize environmental impacts, and underpin the principles of what we now call the circular economy.

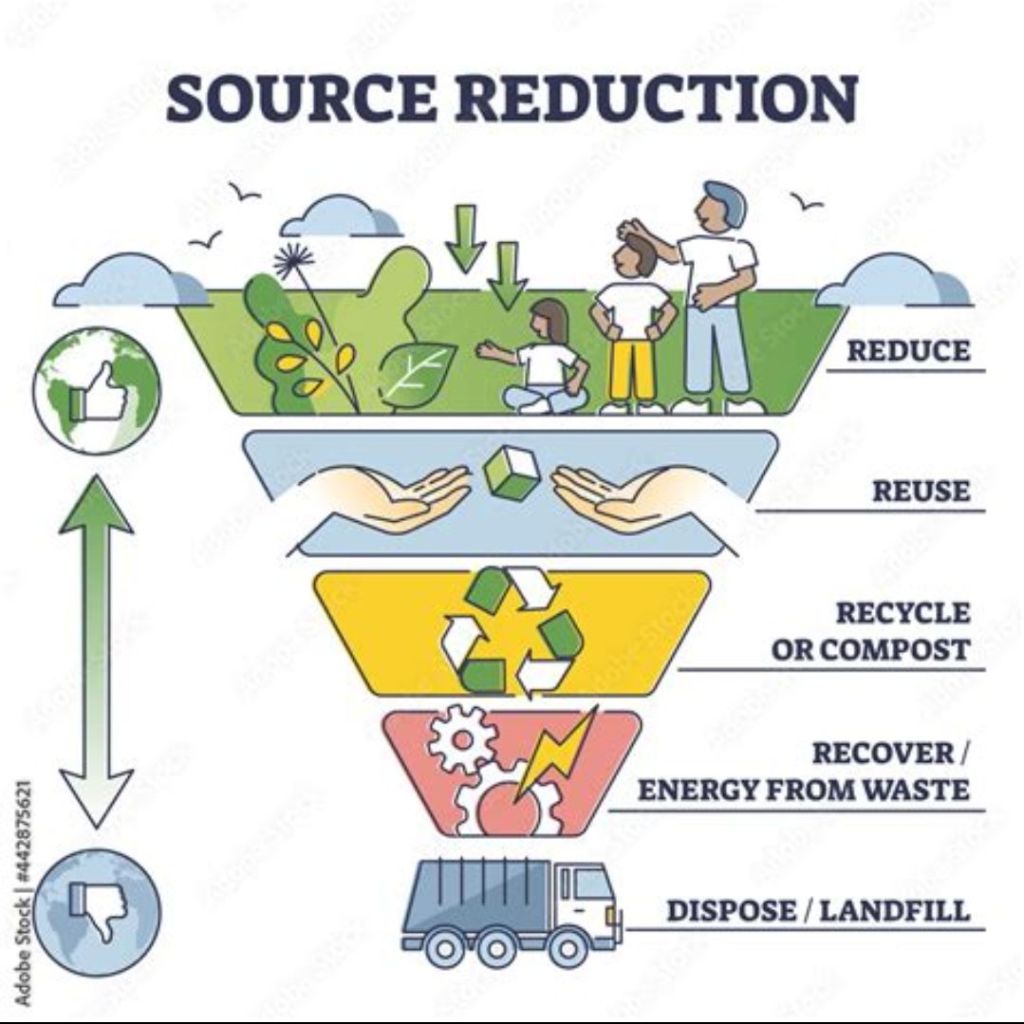

At the heart of this framework was the “waste management hierarchy”—a tool that prioritized waste prevention, reuse, and recycling in a structured order. The logic was simple but powerful: the earlier waste is addressed in its lifecycle, the better the environmental and economic outcomes. This hierarchical model—favoring reduction and reuse over end-of-life solutions like recycling—remains a cornerstone of sustainable product and resource stewardship.

Fast forward to today, and a review of the hierarchy’s implementation reveals mixed progress. While recycling infrastructure has seen significant investment and policy attention, higher-level strategies such as reduction and reuse continue to be underutilized. Despite growing awareness and mounting evidence of the climate and resource crisis, most government initiatives and industry efforts remain anchored at the bottom of the hierarchy—reacting to waste rather than preventing it.

This trend is particularly evident in the allocation of public funding. Grant schemes and incentives often favor end-of-life solutions, like material recovery, rather than upstream interventions that redesign systems and products to avoid waste altogether. The gap between ambition and action widens further when systemic concepts such as reduction and reuse are not fully integrated into commercial practices or policy frameworks.

The updated paper from RMIT’s Centre does more than recount history—it highlights how we must adapt. It urges a renewed focus on frameworks like the circular economy and product stewardship. While not entirely novel, these models offer a pathway to rebalance our priorities. By emphasizing longevity, repairability, and closed-loop systems, they help extend the life of products and materials, thus minimizing resource extraction and waste generation.

This reflection comes at a crucial time. As global resource consumption accelerates and environmental degradation intensifies, a rethinking of how policies are structured is no longer optional—it is urgent. The conversation must shift from managing waste to designing it out of the system entirely.

The challenge is not conceptual—it is operational. We understand the hierarchy. We have the data. What is lacking is the political will and industrial commitment to implement these insights at scale. The authors rightly point out the need for governments and industries to critically evaluate the gap between theoretical sustainability goals and their actual delivery mechanisms.

Ultimately, any meaningful discussion around sustainability and waste management must go beyond technical fixes. It must address the socio-cultural, economic, and political dimensions of consumption and production. The pursuit of ecological responsibility must be paired with policies that are socially meaningful and economically feasible—particularly in a world facing mounting climate risks and resource scarcity.

Leave a comment