Global industry is entering a structural phase shift rather than a cyclical slowdown. What we are witnessing today is not simply uneven recovery across sectors, but the emergence of a two-speed industrial economy. On one side sits legacy manufacturing—capital-intensive, energy-hungry, and optimized for scale in a world that no longer exists. On the other side is a fast-accelerating ecosystem built around artificial intelligence, transition supply chains, and regulatory-aligned production. The divergence between these two worlds is widening, and it is likely to define industrial competitiveness for the next two decades.

Historically, industrial cycles moved together. Steel, machinery, chemicals, and consumer manufacturing rose and fell with global demand, interest rates, and commodity prices. That synchronisation has broken down. Traditional manufacturing is now constrained less by demand and more by compliance costs, energy uncertainty, and capital rigidity, while newer industrial segments are expanding even in low-growth environments because they are embedded in long-term structural transitions.

Legacy Manufacturing: Scale Without Strategic Flexibility

Conventional manufacturing models were built on three assumptions: cheap energy, regulatory neutrality, and globalised supply chains optimised for cost. All three are eroding simultaneously. Energy volatility has become structural, environmental compliance is tightening rather than easing, and geopolitics has fragmented trade routes.

As a result, legacy sectors—basic metals, conventional auto components, bulk chemicals, and traditional machinery—are experiencing margin compression even when volumes hold. Capacity utilisation alone no longer guarantees profitability. Plants designed for maximum throughput are struggling to adapt to requirements for emissions reporting, product traceability, and carbon-adjusted pricing. The problem is not technological backwardness per se, but path dependency: decades of sunk capital make rapid adaptation economically painful.

This mirrors earlier historical disruptions. Just as coal-based industries struggled during the oil and gas transition, today’s carbon-intensive manufacturing faces a long, uneven decline—not a sudden collapse, but a steady loss of strategic relevance.

The Expansion Engine: AI and Transition Supply Chains

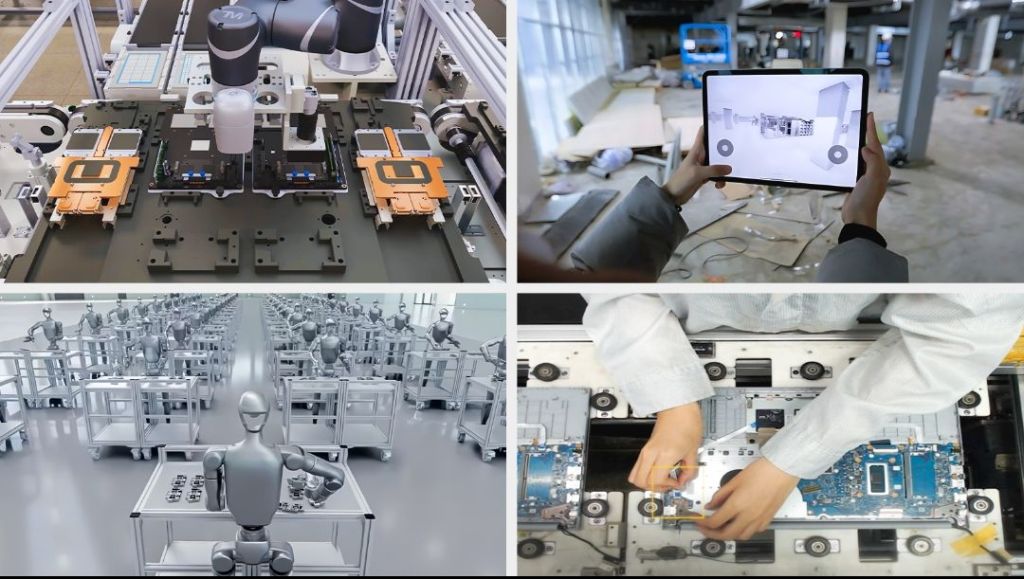

In contrast, AI-enabled manufacturing and transition-linked supply chains are expanding even as traditional sectors stagnate. These include semiconductors, power electronics, batteries, grid equipment, hydrogen-adjacent industries, advanced materials, and digitally optimised factories.

What distinguishes this new industrial core is not just technology, but alignment with policy, capital, and regulation. AI is being deployed not only for productivity gains, but for compliance management, predictive maintenance, energy optimisation, and supply-chain transparency. Transition industries are designed from inception to meet emissions thresholds, localisation rules, and traceability norms.

This is why capital continues to flow into these sectors despite higher interest rates. Investors are no longer chasing volume growth; they are buying regulatory resilience and future market access.

Policy as an Industrial Input

Perhaps the most profound shift is the transformation of policy from a background condition into a direct industrial input. Carbon border adjustments, licensing regimes, localisation mandates, and technology export controls are no longer peripheral—they are shaping investment decisions as decisively as labour costs or logistics.

In practical terms, this means that two factories producing identical goods can face radically different market outcomes depending on their emissions profile, documentation systems, and regulatory alignment. Policy is no longer correcting markets; it is re-architecting them.

Historically, industrial policy was associated with subsidies and protection. Today’s version is more subtle and more powerful. It works through standards, verification, and access rules—mechanisms that favour firms able to internalise compliance costs and penalise those built on thin margins and legacy processes.

Asia’s Next Industrial Battleground: Power at the Factory Gate

Nowhere is this transformation more visible than in Asia. The next phase of industrial competition is not about national grid capacity alone, but about factory-level power control and captive decarbonisation. Reliable, low-carbon electricity is becoming a competitive weapon.

Large manufacturers are increasingly investing in captive renewable power, storage, and energy-management systems to insulate themselves from grid volatility and carbon exposure. This marks a shift from dependence on national infrastructure to self-contained industrial energy ecosystems.

Historically, energy policy was the state’s domain. In the emerging model, firms themselves become quasi-utilities, managing power sourcing, emissions, and resilience internally. Countries that enable this transition through regulatory clarity and grid integration will attract the next wave of industrial investment; those that do not risk losing even existing capacity.

A Futuristic Outlook: From Volume to Validity

The industrial economy is moving from a logic of volume to a logic of validity. Producing more is no longer enough; production must be provably compliant, decarbonised, and digitally legible. This fundamentally alters competitive advantage.

Legacy manufacturing will not disappear, but it will shrink in strategic importance unless it reinvents itself around energy efficiency, digital control, and regulatory alignment. Meanwhile, AI-centric and transition-linked industries will continue to expand, even in an era of slower global growth, because they are embedded in policy mandates and long-term societal transitions.

The future industrial map will not be divided simply between developed and developing economies, but between those that adapt their factories, power systems, and compliance architectures—and those that remain trapped in yesterday’s scale-driven logic.

In this two-speed world, the real risk is not deindustrialisation, but misaligned industrialisation: investing heavily in capacity that the future market no longer rewards.#TwoSpeedIndustry

#AIManufacturing

#TransitionSupplyChains

#PolicyDrivenIndustry

#CarbonCompliance

#CaptiveDecarbonisation

#FactoryPower

#IndustrialFragmentation

#RegulatoryResilience

#FutureManufacturing

Leave a comment